K2 Pakistan Trek

Introduction

‘Shit weather!’ was how a French mountain climber called it when he ducked in out of the rain into our mess tent at Khoburtse. He had just climbed Mount Everest, and was now setting his sights on the most difficult 8000-metre peak, K2.

Succinctly put, I laughed. When I think back to my trek up the Baltoro Glacier in Pakistan, I don't immediately think of the magnificent mountain vistas or the wonderfully hospitable strong local Balti people; no, I think of the weather.

How unpredictable and varied was the weather you may ask? Let's say that I got my money's worth from a t-shirt, light underwear, heavy underwear, trekking tights, shirt, gloves, Gore-Tex jacket and pants all in a single day. Light rain and snow quickly intermixed with sun so strong if you forgot your sun block you could burn to a crisp. The layers come off, the layers go back on again. I realized I must have more fear of being cold than hot, since I usually found I had one too many layers on.

Most days started out around -5C to 0C, but quickly skyrocketed to 15C to 20C when the sun came out. In the late afternoon, the opposite occurred, with the temperature plummeting back to 0C. The temperature remained steady from sunset to sunrise.

The first day arriving in Skardu by plane from Islamabad after flying around Nanga Parbat was perfect. This flight only operates in perfect weather, so it is cancelled more often than it runs. It then got bad for five days with light rain each day.

The weather improved for the two most important days of the whole trip as I watched Masherbrum and K2 in clear sunset and sunrise. The weather then deteriorated again for four days, snowing and even hailing at one point. We trekked to Gasherbrum base camp, but couldn't see anything (I guess I'll have to do with a postcard of G2). I couldn't even go to K2 base camp.

I especially feel bad for a Greek trekker we met going down from Concordia by himself. He had been part of a trekking group who had planned to go over the Gondogoro La. They sat at Concordia for three snowy days and didn't even see a glimpse of K2! He got fed up and left by himself without porters to go back down the Baltoro. I arrived at Concordia the next day with a perfectly clear view of K2. If only he had waited one more day; but, as I like to say 'you can never should have'.

There was a group from Singapore who started the same day I did, but ended up a day behind me. Not only did they not see K2 at all, they also didn't go over the Gondogoro La because it was snowing.

Then again, my guide Iqbal told me he was at K2 base camp in 2000 with a Korean expedition and they had 17 straight days of bad weather.

I got my fourth day of good weather the last day exiting the glacier. I had perfect views of Paiju Peak, Uli Biaho, Trango Tower, Great Trango, and the Cathedral.

As bad as the weather was, I feel I am extremely lucky. If somebody had asked me before the trip to pick four good weather days, I'd have picked the four I got!

Preparation

‘Yeowww!’ I screamed to myself as the two smallest toes on my right foot buckled under my other toes. Trekking accident you ask? No, I had just jumped over a snow bank on the way to pick up my son Peter from school. I hobbled to school, flinching from the pain. I thought how embarrassing it would be to have to delay my planned trek to K2 in Pakistan because of a little snow in Toronto. What if this had happened when I was trekking in the middle of nowhere with absolutely nobody within hours of me? I better not think about it.

I went to my family doctor three weeks later (no need to rush into things) and discovered I had broken the two smallest toes. They were healing nicely.

I kicked my training into high gear, running, cycling, walking, and climbing a small hill near my home (many times of course). I was ready!

I started my research by buying many books, including K2 Dreams and Reality by Jim Haberl, In the Throne Room of the Mountain Gods by Galen Rowell, and K2 Challenging the Sky by Roberto Montovani and Kurt Diemberger. I learned that the trek was just amazing and that K2 was probably the most beautiful and dangerous mountain in the world. I was hooked.

The Karakoram (‘Black Mountains’) and Himalaya are the newest mountains in the World. About 55 million years ago, the northward drifting Indian geological plate collided with the Asian Plate, its northern edge nosing underneath the Asian Plate and pushing up the mountains. The Indian Plate is still driving northwards at about five centimetres (two inches) per year, causing the mountains to rise about seven millimetres (1/4th inch) in the same period. Pakistan has the largest concentration of high mountains in the World. There are more than 100 peaks over 7,000 meters within a radius of 180 kilometers. Five of the 14 8000-metre peaks in the world are in Pakistan. Peaks above 3,000 to 6,000 meters are countless and remain unclimbed and unnamed. Out of 100 highest peaks in the world, more than 50 are in Pakistan.

K2 (8611m) is the second highest mountain in the world, and is thought by many climbers to be the ultimate climb. Its giant pyramid peak towers in isolation, 3900m above the wide Concordia glacial field at the head of the Baltoro Glacier. In 1856 Capt. T.G. Montgomerie of the Great Trigonometric Survey of India saw a cluster of high peaks from a point 137 miles away in Kashmir, and entered them as K1, K2, K3 and so on, with K standing for Karakoram. K2 is the only major mountain in the world that has the surveyor's notation as it's common name. The mountain's remoteness had rendered it invisible from any inhabited place, so apart from an occasional local reference as Chogori (meaning Great Mountain or Big Snow Mountain), it had no other name prior to Montgomerie's survey. Since that time, the name Mount Godwin-Austen has occasionally been used, in honour of the man who directed the survey. For the most part, however, K2 has been the name of choice, and has even evolved into Ketu, the name used by the Balti people who act as porters in the region. The sheer icy summit is flanked by six equally steep ridges. Each of its faces presents a maze of precipices and overhangs. K2 was long considered unclimbable. Attempts in 1902, 1909, 1934, 1938, 1939 and 1953 all failed. The first successful ascent in 1954 was by the Italians. It started with over 500 porters, 11 climbers, and six scientists. One of the climbers died of pneumonia after 40 days of raging storms. The final ascent was made by a team of two after their oxygen supply had run out, and an emergency descent was made in darkness.

I read about each mountain and expanded my planned trek to include all five of Pakistan’s 8000-metre peaks.

After my success using the Internet to plan and book my Mt. Kenya / Kili trek, I decided to try the same thing again. I did many Internet searches and sent emails to various tourist agencies, mostly in Islamabad and Gilgit, looking for a customized personal trek. The prices were very good compared to the standard group treks offered by U.S. or British companies. It looked like about $70-80 U.S. per day would do the trick. I booked with Trango Adventures in Rawalpindi. I then booked my flights through my local travel agent Niaz, and then confirmed my trek with Trango Adventures in Islamabad. The cost is $70usd per day, totaling $1750usd for 25 days for everything from the time I land in Islamabad until I get back to the airport. And it’s private too.

Day 0 Fly To Islamabad

I flew via Frankfurt and Dubai to Islamabad. The Emirates airplanes had the latest in personal entertainment. There were 15 channels for movies and TV, one that shows the flight map, one that shows the camera from the front of the airplane, one that shows the camera below the airplane, and 20 channels for music from western pop, jazz, country and classical music to Hindi and Thai favourites. There were also 14 games from checkers and chess to blackjack and poker.

My tour company Trango Adventures picked me up at the airport and drove me to the Paradise Inn in Rawalpindi, where I had a late dinner in the warm evening air.

Day 1 June 11 Islamabad

Islamabad, the capital of Pakistan, is located against the backdrop of Margalla Hills at the northern edge of Potohar Plateau. The word ‘Islamabad’ is Persian for ‘inhabited by Islam’. In contrast to its twin city Rawalpindi, it is lush green, spacious and peaceful. The master plan of this most modern city was prepared in 1960 by M/S Constantions Doxiades, a Greek firm of Architects. Construction was started in October 1961. The city came into life on October 26, 1966, when the first office building of Islamabad was occupied. It is a modern and carefully planned city.

Rawalpindi was originally known as Fatehpur Boari. It was destroyed during the 14th century by a Moghal invasion and remained deserted for a number of years. 350 years ago, during the reign of Emperor Jehangir, a sikh by the name of Rawal Jogi came to the deserted Fatehpur Boari and was instrumental in recreating the glory of the city. In appreciation, the town became known as Rawalpindi. Sikhs lost the city to British in 1849. It then became the General Headquarters of British Army and they established a cantonment south of the old city. The ‘Cantt’ is still headquarters of the Pakistan army.

Before I left home I would jokingly say that my guide's name would be Muhammad. Sure enough, my guide introduced himself as Muhammad Iqbal. ‘But just call me Iqbal’, he requested. Iqbal later told me I had an 80% chance because 80% of Northern Areas boys have Muhammad as their first name. If we did the same thing in our western Christian society, I'd be Jesus Jerome Ryan, but you can just call me Jerome. This is his fifth year of guiding.

We drove through the hectic streets of Pindi and through tree lined deserted roads to Islamabad. We drove by some of modern buildings in Islamabad, the most notable being the National Assembly Building using Moghul architecture, and the home of the President; known as Pakistan House. Siddiq asked the policeman if I could take a picture and he said 'No, not since the military took over the government.

Our first stop was in a somewhat dilapidated building next to a football stadium, the ministry of Tourism. Every trekker needs to go through a trek briefing. I sat down and waited for the Ministry or Assistant Ministry to call me in. While I waited, I looked around at the posters on the walls, some signed by the mountaineers. Iqbal talked to the man behind the desk who gave him some paperwork, a total of five copies. The door to the ministry opened and an unassuming Pakistani man with a westerner came out. Iqbal leaned over to me and whispered, ‘That’s Ashraf Aman, the Managing Director of ATP.’

‘Oh yeah, I emailed them, but they were too expensive.’ I commented.

‘He’s quite famous here in Pakistan. He was the first Pakistani to climb K2 way back in 1977!’ Iqbal stated. ‘He’s been guiding climbing expeditions for many years. His company is also the biggest trekking company in Pakistan.’

Iqbal spoke to the man behind the desk for a minute. ‘That man who came out is a German who’s leading an international group trying K2. Ashraf is arranging it.’ I was later to learn that the German was Peter Guggemos who at that time had climbed Nanga Parbat, Gasherbrum I and II, Broad Peak, Cho Oyu and Shishapangma.

We drove up to the 1100m low hill overlooking Islamabad, known as Daman-e-Koh to get a panoramic view of Islamabad. It's a pity it's so hazy, otherwise it would have been beautiful.

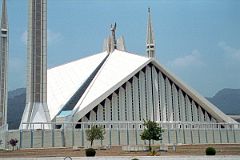

Built in 1985, the beautiful Shah Faisal Mosque in Islamabad was designed by a renowned Turkish Architect Vedat Dalokay, and named after late King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, who donated most of the US$50 million cost. The Shah Faisal Mosque in Islamabad is spread over 189,705-sq. metres with 88m high minarets and 40m high main prayer hall. The main prayer hall can accommodate 10,000 persons while the covered porticoes and verandahs can take over 24,000 worshipers. The main courtyard has space for 40,000 people.

Day 2 June 12 Fly To Skardu

The adventure begins with the 40-minute flight from Islamabad to Skardu.

‘We'll be flying at a planned altitude of 8,000 metres’, the captain said. Perfect I thought, we'll be exactly at the height of Nanga Parbat.

The flight starts low key with the stewardesses serving drinks while we bide our time. When the pilot announces ‘Nanga Parbat is immediately ahead on the right’, all hell breaks loose. As one, all the tourists, including me, are up in the aisles, craning their necks, running for the cockpit. The sounds of cameras are everywhere.

Iqbal motioned me to an area where there are only two seats with room for two people to sit on the floor. There it is, within arm's reach. Nanga Parbat in perfect early morning splendor! We are passing by the northwest face, as I click photo after photo.

After passing by the Diamir Face, we can see Hermann Buhl’s route of first ascent with the Rakhiot Peak leading up to the Silver Saddle between the Nanga Parbat Southeast and East Peaks, and up to the summit with the North Peaks on the right.

Fosco Maraini wrote a perfect summary of the ascent in Karakoram: The Ascent Of Gasherbrum IV: "A mountain so savage, a killer of 31 men (14 Europeans and 17 porters), could yield, in the end, only to a splendid folly. The madcap was a little Innsbruck Austrian called Hermann Buhl. Alone, he reached the summit in 1953. He disobeyed the leader’s orders, for 40 hours he forced a passage over ridges and cornices – all the time above 26,000 feet. He kept himself alive, like the maniac he was, on a few tablets. He spent the night crouched in a hole in the ice, like a wild beast. Not only had he no sleeping-bag, he had no special kit; visited by strange hallucination, he just pressed on. His crampons worked loose; no matter, he tied them to his boots with a string. Onwards, upwards! Nothing to drink, nothing to draw on but his own stupendous courage, and blessed by one sole clemency from Fate – forty hours of no wind and no cloud. The giant peak was happy to welcome such a man as her own, and to accord him such glorious privileges."

Another tourist (a climber I met later in Khoburtse) wants in, and I switch to the left of the plane with a sweeping view of the Karakoram Range. I can see a very large mountain in the distance - K2! The plane turns right and flies over the gorge of the Indus River, over Skardu and doubles back to reduce altitude and we land. I'm exhausted! And it's only 10 am.

Skardu is the district headquarters of Baltistan, situated on the banks of the mighty Indus River, just 8 km (5 miles) above its confluence with the Shigar River. Perched at a height of 2286 metres, Skardu sits below magnificent mountains. The Indus barely seems to move across the immense, flat Skardu valley, 40km long, 10 km wide and carpeted with sand dunes. There are several beautiful blue lakes nearby, including Satpara, and Upper and Lower Kachura.

After landing at Skardu, our jeep stopped at a gas station to refuel and then we drove down the main streets of Skardu to the Concordia Hotel, beautifully situated above the banks of the Indus River. It was stinking hot (38C) when I got to the Hotel, so I enjoyed a cold Pepsi before descending from the hotel to the Indus River, where I skipped flat stones on the calm waters of the Indus.

The Indus River snakes around Khardong Hill with the Kharpocho Fort, seen from the Concordia Hotel in Skardu.

I walked through the Chumik area of Skardu village below Khardong Hill, waving at the kids who asked me for 'pen, pen'. I wonder if they teach Tourism 101 in primary schools in third world countries. Teacher: ‘Now class, today we learn about western society guilt. If you ask them for chocolate, they will think they are harming your teeth. But if you ask for a pen, they will feel guilty that they have so much and you need a pen to go to school. It'll work almost every time.’

Teacher: ‘If they won't give you a pen, try looking cute, but dirty. Tourists love cute dirty children. When they take out their camera, ask for one rupee for photo, say after me class, 'photo, one rupee'‘. I guess I have no guilt and no pens, and no need for a photo of a cute dirty child because I simply smiled and walked on. Please practice responsible tourism.

I climbed a little up the Khardong Hill to get a view overlooking Skardu, with the way to Satpara Lake behind. I walked back down the main street of Skardu to the Concordia Hotel for lunch.

After lunch Igbal and Muhammad Ali came by and we drove for about 20 minutes from Skardu up to see the beautiful crystal clear water of Lake Satpara.

Muhammad Ali was the cook on the K2 trek. He is 22 from near Gilgit. He speaks English, six of the Pakistani languages, and is studying Japanese in University. He chose Japanese because 60% of the tourists to Pakistan are Japanese. He is friendly, very funny and a bit of a kidder, and a great cook.

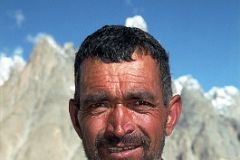

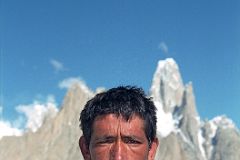

My guide Iqbal is a 23-year-old Balti from Skardu. We went to Iqbal's house. They have six rooms, and are building an addition for two more rooms. There are 24 people living there, including the extended family. They have a large backyard, with flowers and vegetables.

I also met a man who Iqbal explained is not a family member. ‘We have two jeeps’, Iqbal explained, ‘and he is our driver!’ Very few people in the west have a chauffeur, I thought to myself. Rich in some ways, poor in others.

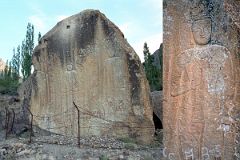

Buddhism once flourished in Baltistan and Iqbal said we would stop and see the cultural relic known as the Buddha-rock.

On the drive back to Skardu from Satpara Lake, the driver took a rough side road for 15-20 minutes. We arrived at an ancient large rock carved with Buddhist images in the seventh or eighth century.

Buddha sits serenely on the rock carvings flanked by attendants. This historical monument is unguarded with just a little barbed wire.

On our way back to Skardu in the late afternoon, the weather cooled and the late evening sun illustrated the shapes of some photogenic beautiful, silvery-grey sand dunes.

We then drove back to the Concordia Hotel. I enjoyed the garden and could see a constant companion on the trek ahead – an army helicopter flew past me. I then had dinner in the dining room and sat in the garden again, relaxing before having a last good night's hotel sleep.

Day 3 June 13 Drive Skardu to Thongol

In the morning we pack the jeep with provisions and people (guide, cook, and four porters) for our seven-hour 117km jeep ride from Skardu to the trailhead at Thongol (2850m).

Balti porters are every bit as strong as the Sherpa people of Nepal, and that is saying something. They make their own wooden backpacks to support the 25-kilo loads each carries, a weight limit imposed by the Pakistan government. Yet they seem unfazed by the rugged trails that follow the river valley ever deeper, and ever steeper, into the mountains. The porters are agile, tireless, hardworking people who ferry massive loads of gear on their backs. Like the more familiar Sherpa people of the Himalaya, the Balti people originated in Tibet. Over 600 years ago they migrated to the Karakoram. Originally Buddhist like the Sherpas, the Balti converted to Islam during the Moghul insurgence of the 16th century.

Ali Naqi (just call me Naqi) is the sirdar, leader of the porters. He is 47 from Khaplu and has eight children. He has worked for 17 straight years with a famous Japanese photographer, Fujita, and will again this year. The photographer tipped him for the first time last year after 16 years with no tips (Ali explained that tipping is unheard of in Japan). After dinner for three nights on the K2 trek, Naqi told us a local story. It concerned the birth of a baby boy, Gulbaharem, and his search for a wife, Gulbaree, when he grew up. I met Naqi again at Iqbal's house in Skardu. He was going home to Khaplu on the next day because his 16-year old daughter was getting married in a week. I asked how many people will attend the wedding. Naqi said about a thousand. But his total cost will only be about 5000 rupees ($90usd).

Muhammad Khan is a 45-year old porter with two daughters and lives in Skardu. He is originally from a small village near the Indian border. During the 1971 war with India, his grandmother led the local women to help supply the Pakistani Army. When the Indian Army overtook their village, they moved to Khaplu. After the war, Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto wanted to do something for this great woman. He sent her clothing and food which she selflessly distributed to the villagers. Later, Bhutto flew into Khaplu to thank the grandmother for being such a patriot, but she had recently died. He asked the villagers ‘What do you want?’ They replied ‘Nothing. We don't need anything from the government. The people of Khaplu have given us shelter and food.’ Ten years later the government offered them free land in Skardu and they moved. They worked hard, built houses, and now have a good life. He now has two houses and rents one.

Muhammad Siddiq is just 19 years old and is a porter for the first time. He is from Kachura (near Skardu). Although the crew jokingly call him a city-boy, he impresses me with his strength and determination on his first trek to Baltoro.

He doesn't want to be a porter again. He might be an assistant guide for Iqbal's next tour group. He wants to join the army when he finishes college.

After returning from the trek, we drove up to the see the clear water Of upper Kachura Lake and the Chinese pagoda style buildings Of Shangri-La resort on lower Kachura Lake and I had the pleasure of visiting his house and meeting his mother.

We stop and admire the view ahead to the green oasis of Shigar, following the swift flowing Shigar River upstream.

We stop briefly in Shigar to visit the Amburiq Mosque, built by Kashmiri craftsmen in the 14C. The building was being restored by Aga Khan Foundation. The mosque has a double layered roof structure. The base roof is flat in shape and was completely built by juniper wood. The top roof is gabbled and has a Tibetan tower on top.

The road up the Shigar Valley to Dasso is over a fairly good gravel road with a picturesque rock tunnel. We first drive through the Shigar Valley where apricots are a specialty.

At Dasso we crossed the Braldu River on a 100m suspension bridge. The bridge swayed up and down as the jeep crossed the creaking wooden bridge suspended by steel cables.

And then the excitement begins – the 40km Braldu Gorge!

The road is blasted out of the rocks next to the roaring Braldu River as we drive through the Braldu Gorge towards Askole.

We drive along a sickeningly narrow gravel road, sometimes slanting dangerously towards the Braldu River through the exciting Braldu gorge. Exciting that is if you love being scared constantly for two hours with your life clearly in your driver’s eyes, hands and feet. 'Oh well', I thought. The scariest thing for me was when the jeep had to do three-point turns around hairpin curves. He'd get to the edge with the foaming Braldu River hundreds of metres below, and then reverse back up the hill. 'I hope he knows the reverse gear', I think to myself.

I can see that parts of the road were fairly easy to carve out of the mountainside since it has the consistency of chalk. It looks like you could pinch it between your hands and it would disintegrate to dust. But this would also release the rocks being loosely held. I can see why landslides are so common. We stop the jeep and two of the porters ruin up the road to make sure that there is no oncoming traffic – we won’t be able to pass each other on the narrow road hemmed in by the Braldu River and the side of the Braldu Gorge.

Our driver suddenly stops and says, ‘No can go further. New jeep here’. The small bridge across a small side stream has been washed out. We cross the river on a small footbridge, the porters carrying everything to the other side where it is put on a waiting jeep.

We continue our road journey on the new jeep, and after about 30 minutes cross the final bridge just before Thongol. ‘Sometimes, we have to switch jeeps five or six times’, Iqbal explains, ‘and then it can take 12 hours.’

We arrive in Thongol and quickly unload the jeep and set up the kitchen tent and my tent where I rest for a few minutes. Ahhh.

Iqbal puts together the loads a little bit like a jigsaw puzzle trying to even them out to 25kg each. There are nine loads so Iqbal has to find five more porters. He tells me he's having trouble because the porters want to wait for the mountaineering expedition we met on the flight to Skardu.

We pause at Thongol for a team photo before we start the trek the next day: below - Jerome Ryan, guide Iqbal, cook Ali; above - porters Syed, Muhammad Khan, and Muhammad Siddiq, and finally our sirdar Ali Naqi.

Day 4 June 14 Trek Thongol to Jhola

On June 14 at 07:15, the 135km trek to K2 Base Camp begins -- a long caravan of Balti porters from many trekking groups and mountaineering expeditions, my cook Ali, and I wind our way out of Thongol and up the Braldu River Valley. The Braldu drains the world's longest non-polar glacier, the Baltoro, a 62-kilometer river of ice reaching into the heart of the Karakoram. After an hour walk we pass thru the last village, Askole (3000m) with beautiful fields shining in the morning sun.

The temperature quickly increased to 30C as we trekked from Askole above the Braldu River. The easy trail ran out and we had to climb steep steps cut into a rock to continue the trek from Askole towards Korophon, with views ahead to the glacier below Choricho (6756m).

Just after the stone steps, I crossed a small bridge over a river emerging from the Biafo Glacier. I wasn't prepared for the 30C+ weather and drank my last water just after crossing the bridge.

I could see the long trail ahead crossing the end of the Biafo Glacier. I struggle on in the heat getting slower and slower. I'm getting severely dehydrated and am overheating. I sense we're getting close to Korophon, but I have to rest. But it's too hot to sit for very long. So I scramble to my feet and continue even slower. I'm starting to shuffle my feet. We finally come to a small stream coming from the Biafo Glacier. The other porters are drinking the water, and motion me to follow suit. I drink a litre of the cold refreshing water. I guess it is safe because nobody lives up the glacier.

I happily continue for five minutes to Korophon (3000m) where we stop for lunch, but many people camp. Korophon (3000m) is a small tree-filled oasis at the snout of the Biafo Glacier. The view up the glacier is part of the Baintha Brakk massif.

‘Do you like fresh mango juice for lunch?’ my cook Ali asked with a sly smile at our lunch stop at Korophon. ‘I think so,’ I responded hesitantly. ‘You don't need a bottle, can or glass, no machine or electricity. You can make absolutely pure fresh mango juice anywhere, even the desert, the jungle or on the top of K2. It only takes a minute,’ Ali boasted. ‘Impossible. Show me,’ I challenged him.

So Ali gets a mango and starts squeezing it. After a few minutes he bites off the top and gives it to me. ‘Just squeeze and suck in,’ he tells me. It's excellent. I squeeze all the juice out. Ali then shows me to make a slightly larger hole at the end and take out the pit and suck it like an ice cream cone. Fantastic.

After lunch the trail from Korophon goes along the river and then climbs high above the river. We stopped briefly to rest in a cave. The trail followed the course of the Braldu River with a view ahead to the trail from Jhola to Paiju contouring around the hill and then turning to the left.

The trail from Korophon to Jhola was being improved by blasting through the cliff face. Previously people had to rope up and cross on a dangerous high path. And the work still continues.

After reaching the junction with the Dumordu River coming from the Panmah Glacier, I walked up alongside the river and crossed the river on a new footbridge. It was rather crude with bits of trees nailed across with many holes.

The bridge over the Dumordu River to Jhola campsite is not as exciting as the famous wire pulley system that used to be in place – a small wooden box used to hang from a steel cable. One by one, porters, gear, trekkers, and goats got in and were pulled across the river.

After crossing the bridge over the Dumordu River, it was a short walk to Jhola campsite. Ali and I sat down, relaxed, and waited for the rest of our crew. Ali Naqi and two of our porters arrived at Jhola campsite an hour later. Our third porter, Muhammad Khan, arrived in a little over an hour. He waited at Thongol for Iqbal to hire the additional five porters. But at 11:00 he figured we'd at least need the tents so he left.

They quickly set up my tent and I crawled in and rested and read. I left at 20:00 to go to the mess tent for dinner.

It was lightly raining. I couldn't find it. I found Ali and the four porters huddled around a bush fire cooking my dinner.

Not only did Iqbal not show up, but we didn't have the mess tent either. I went out an hour later and found where they were - all five were sleeping in a 2-person tent! Ali explained that a friend had an extra tent.

Day 5 June 15 Trek Jhola to Paiju

The next morning Iqbal and five porters arrived at 6:00. Iqbal told me his story. Iqbal gave up at 12:00 trying to find porters in Thongol. They all want to wait for two large expeditions, which will arrive later in the afternoon. He grabbed a jeep back to Apo Ali Ghon, a village about two hours up the road from Thongol, arriving there at 15:00.

He walked into a house where a woman was crushing wheat. She asked ‘Why are you here and where are you from?’ Iqbal told her he is a Balti from Skardu. Then she softened up and made him some chapattis and tea. He told her he needed porters for trekking. Her husband came home and he helped Iqbal find the other porters, and he came along too. They left at 17:15 and reached Thongol at 19:00. They left Thongol at 19:15 and walked in the dark to Korophon. An army soldier talked to Iqbal and loaned him a flashlight. When they reached the really steep section, they huddled in a cave until the moon came out at 3:45. They then continued the rest of the way to Jhola.

One of the porters Iqbal was able to hire joined our crew for the entire trek. Hayder Khan is a 30 year old porter from near Shigar. He has three children and is very quiet and shy.

However, when egged on by Ali, he sung a Balti song with great enthusiasm and skill. He has been a porter for eight years. If he gets lots of porter jobs, he can make 15-17,000 rupees in a year ($2500 - $3000usd); if he doesn't, he might make only 7000 rupees ($1200usd).

After leaving Jhola campsite, the trail once again climbs above the river on a dizzying trail carved out of the rock face. I could see the army blasting the rock face to improve the trail just after Jhola campsite.

The trail descends from the rock face and goes along the Braldu River for a while. The trail then alternates from a nice easy trail to having to be very careful as the trail slopes inches down to the Braldu River.

The swollen river flowing down from the Paiju Glacier blocked our way as we neared Paiju. I slowly stepped into the fast flowing river with Naqi holding me all the way. I was relieved to reach the other side of the river. I then watched as Ali and Naqi helped the porters and Iqbal cross the river. The trail then turned and, walking next to the Braldu River, I could see Paiju (3450m) ahead and the spires above the Baltoro Glacier.

After setting our camp at Paiju (3450m), I walked through Paiju, watching the Balti porters cooking, used the latrine built by the Central Asia Institute, and then walked farther ahead to see the trail to the Baltoro Glacier.

The weather started to clear at Paiju in the late afternoon. I was admiring the Cathedral and a bit of the Lobsang Spire in the late afternoon from Paiju when I noticed a tall peak far away poking out in the distance. I strained my eyes and couldn’t believe it – it’s K2.

I climbed a bit higher above Paiju and eventually the West face of K2 came into view just before sunset. The next morning I once again was able to see K2 poking above Lobsang Spire.

Day 6 June 16 Trek Paiju to Koburtse

Just before starting the trek on the Baltoro Glacier, I could see where the Braldu River begins as it comes out from under the glacier. The Baltoro is more than two km wide and 68km long. It starts with ice cliffs towering more than 100 metres above. After walking alongside the Braldu River, I step onto the Baltoro Glacier at 12 noon on June 16, 2001.

The Baltoro Glacier doesn't look like what you would imagine - it's full of rocks and gravel. However, as soon as you see a section cut away, you can see that the true ice is just a few inches below. It creaks and groans, with water dripping as it melts, and frequent rock slides.

After beginning the trek on the Baltoro Glacier, the view included Uli Biaho, Trango Nameless Tower, and the Great Trango Tower. Then the many spires of the Cathedral Group (5866m) were silhouetted perfectly.

The Trango Tower (6239m), commonly called Nameless Tower, is a very large, pointed spire which juts 1000m out of the ridgeline. The Trango Nameless Tower was first climbed in 1976 with Mo Anthoine, Martin Boysen reaching the summit on July 8, 1976 and Joe Brown and Malcolm Howells the next day.

The Trango Monk (5850m) came into perfect view to the north of Trango Nameless Tower as I continued trekking up the Baltoro Glacier. Tomaz Jakofcic and Miha Valic made the first ascent of Trango Monk (5850m) on September 7, 2004 via the east and south faces.

Then the whole Trango group came into view: Trango Ri (6363m), Trango II (6327m), Trango Monk (5850m), Trango Nameless Tower (6239m), Great Trango Tower (6286m) and Trango Pulpit (6050m), and Trango Castle (5753m).

Great Trango was first climbed on July 21, 1977 by Galen Rowell, John Roskelley, Kim Schmitz, Jim Morrissey and Dennis Hennek by a route which started from the west side (Trango Glacier), and climbed a combination of ice ramps and gullies with rock faces, finishing on the upper South Face.

We trekked up and down the rubble-cover Baltoro Glacier, resting every now and then. I then climbed above a large lake on the Baltoro Glacier amid some grass and small flowers with Trango II, Great Trango Tower and Trango Castle behind – simply spectacular.

Just before we reached Khoburtse, Lobsang Spire came into view behind the spires of the Cathedral Group.

We camped at Khoburtse (3930m).

Day 7 June 17 Rest Day At Koburtse

The next day was overcast and rainy, so we decided to stay another night at Khoburtse. I simply lazed around in the mess tent talking and reading. Suddenly, a face popped in and asked if he could come in out of the rainy weather. Ali jumped up and invited him in and offered him some tea and cookies, which he readily accepted. The man was tall and looked like he was in his mid-30s. He introduced himself as Christian Trommsdorff, a mountain guide from Chamonix in France. He had just summited the North face of Everest on May 22, 2001 without oxygen, but got stuck in Kathmandu with the massacre of the Royal Family. Luckily he got out in time to join the German International Expedition. He told me he wanted to summit K2 by himself, without Sherpas or oxygen. I asked him about other 8000ers and he said he had summited Cho Oyu in 1997. Within minutes of the tea and cookies coming, they were finished. Ali ran off to get more. Christian was funny, opinionated, and very interesting.

Two other men came in to our kitchen tent at Khoburtse to get out of the rain. The first was a friendly man who looked a bit like a rock star with long hair and a beard. He told me his name was David Jewell from Wellington, New Zealand and that this was his first attempt at K2, but that he had summited Cho Oyu in 1997. He told me he was a computer systems analyst from Wellington. I told him that I too used to be a Mainframe Software Systems Programmer. Christian piped up that he also was a computer programmer until he gave it up to become a full-time mountain guide.

Thirty minutes later, another man popped his head in, and recognizing Christian, came in and introduced himself, ‘Hi, I’m Peter Grote.’ I sized him up and decided he didn’t look like a mountaineer. ‘Oh no, I’m a photographer. I’m tagging along on the expedition, but I plan to take some amazing photos of the summit teams.’ He told me he uses large format camera with an extremely expensive enormous lens. ‘I can take a photo of a man on the summit and even see the markings on their ice ax’, he proudly stated. The lens is so large and powerful that he needs a tent just to house the lens. He planned to have two porters accompanying him to the saddle.

Three more men came in out of the rain. I recognized the first man as the leader of the expedition I had seen in Islamabad. He introduced himself as Peter Guggemos, and introduced the other two men as trekkers. The trekkers looked a little worse for wear and seemed to be struggling. Peter was a tall thin man with short-cropped hair and a beard who looked lean and muscular and in his early 40s. I immediately liked him. I asked him if this was his main form of living. ‘No, climbing is my hobby. I have a fairly large construction company in Germany, which my wife is managing while I’m away.’ I told him that trekking was my hobby, and that I especially loved Everest and I had been to all three sides.

A short muscular man poked his head in, said hello to Christian and Peter, but decided to continue on to their camp. Peter told me, ‘That’s Jean-Christophe Lafaille. He’s probably the best mountaineer in Europe right now.’ I asked Peter how many mountaineers would be on the Expedition, and he answered ‘We have another member who will join us at base Camp. It’s Hans Kammerlander. This is his third attempt at K2, and Hans says it’s his last, so I hope he makes it this time.’ After relaxing, getting dry and having some tea and cookie, they left as they had arrived, one by one. I was sorry to see them go, having enjoyed their company, and breaking up my monotonous day.

After I got home, I used the Internet to find out how they did. Peter Grote had to be helicoptered back from Base camp a week after I met him with an eye injury. David Jewell turned back above 7000m. Christian turned back above 8000m. Peter Guggemos turned back at 8200m, Hans Kammerlander and Jean Christophe Lafaille summited together. This was Hans’ thirteenth 8000er, and Jean Christophe’s seventh.

Day 8 June 18 Khoburtse To Goro II

The weather was clear in the morning and I climbed a little above our camp at Khoburtse to watch the morning light on the mountains and spires. Just before the sun came up I had a clear view of Paiju Peak, Choricho, Uli Biaho Tower, Trango Castle, Cathedral and Lobsang Spire.

The rays of sunrise hit Choricho first. Choricho (6756m), also called Paiju North, was first climbed by Ian Wade, Michael Goff, Geoffrey Childs, and William Miller on August 1, 1979 via the southwest face and west ridge.

Paiju Peak is a beautiful mountain, seen from Khoburtse. Paiju Peak (6610m) was first climbed by Bashir Ahmed, Nazir Sabir and Allen Steck on July 21, 1976.

Uli Biaho Tower shines in the early morning sun from Khoburtse. The first ascent of Uli Biaho Tower (6109m) was made on July 3, 1979 by John Roskelley, Kim Schimtz, Ron Kauk and Bill Forrest via the east face.

‘One by one, each of us climbed to its broad top, soaked in the evening’s warmth, cried a little, laughed a little, and, for just a few brief moments, forgot the cold, thirst, and danger below.’ - Stories Off The Wall by John Roskelley.

The Trango Towers are a group of dramatic granite spires located on the north side of the Baltoro Glacier.

The Towers offer some of the largest cliffs and most challenging rock climbing in the world. The highest point in the group is the summit of Great Trango Tower, 6,286m.

Trango Castle (5753m) looking like a castle is the last large peak along the ridge before the Baltoro Glacier.

Biale Peak (6729m) was first climbed by a Japanese expedition in 1975. Masaki Aoki: 'Our expedition consisted of Fumiyoshi Shigematsu, Tokiyoshi Kimura, Chitose Okada, Mikio Hamada, Tadanori Ochiai and me as leader. Base Camp was on the right bank of the Baltoro Glacier near the junction of the Mustagh Glacier and opposite Rdokas. The south and southwest faces of Biale were so steep and dangerous that we avoided them and advanced our camps up the Mustagh Glacier toward the snow-covered north face. Fortunately our route was rather easy because we could find a route on ice and snow without the steep rock characteristic of the nearby Trango and Payu groups. On July 21 Shigematsu, Kimura, Hamada and Ochiai set up Camp III west of the peak on the col between the Mustagh and Kruksum Glaciers and on the 22nd climbed the 2500-foot snow and ice west face to the summit (22,077 feet). The only woman in the party, Okada, and I climbed to the top on July 24.'

The Cathedrals are a complex collection of rocky spires overlooking the Baltoro Glacier and rising above the east bank of the lower Dunge Glacier opposite the Trango Group.

The first recorded climb was by Jim Beyer, who in 1989 soloed a 54-pitch 13-day line off the Dunge Glacier to the summit of Thunmo (5866m), which lies south of Cathedral Spire.

Lobsang Spire was first climbed on June 13, 1983 alpine style by Doug Scott, Greg Child, and Pete Thexton.

‘It’s featureless up there. Impossible,’ says Doug. …Out comes the drill. … For two hours I hammer away on the fifteenth pitch, interspersing rivets with sequences of skyhooks balanced on tiny edges, in order that our ten rivets might last the 100 ft to the summit. When I step onto the final skyhook placed on the lip of the knife-edged summit I grab a handful of snow and sprinkle it onto Pete And Doug below. ‘A present from the summit,’ I shout.’ - Thin Air: Encounters in the Himalayas by Greg Child.

We left Khoburtse and trekked along the rubble-strewn Baltoro Glacier. ‘This glacier is altogether the most inhospitable we have seen. Not only is its surface wholly stone-covered and horribly mounded, but its sides are steep and always difficult to traverse; they are exceptionally barren, with little grass and almost no fuel.’ - Climbing and Exploration in the Karakoram Himalayas by William Martin Conway (published 1894).

There are a few ice penitentes on the Baltoro Glacier, including large rocks resting precariously on the ice pedestal. The ice melts in the sun around rocks but not under the rocks where there is shade.

The trekking trail is well maintained by the Pakistani Army. Because of the tension between Pakistan and India in these high mountains, the army has nine camps situated on the trekking route all the way to their high camp overlooking the Siachen Glacier. The supplies for all camps, except the last two, are carried by horse and mule trains using the trekking trail. For the two high camps helicopters are used.

A black telephone wire snakes along the ground all along the trekking route from Thongol to Concordia and Gasherbrum Basecamp. It was strung in 1986, when the Indians strung a similar one up the Siachen Glacier. Just clip into the rope with your jumar and you're set (just kidding, you might choke the military conversation and remember they have guns and you don't).

If you follow the wire, there are only three spots to be careful. The first is just before the Paiju campsite where the wire crosses the Braldu River to the army camp on the other side. You don't want to be rushed down the river to where you started your hike, now do you. The second is only a slight detour to the Goro I army camp, which is the headquarters (base camp so to speak) for the Baltoro Glacier camps. The third is at Concordia. Since there is no army camp at K2 base camp, if you follow the wire you will see Gasherbrum Base camp, not K2. Most people prefer K2, but it's up to you. Iqbal mentioned he had to use the wires in May a few years ago when there was still a lot of snow on the ground. They simply pulled the wire up from the snow and followed it.

We trekked each day five to six hours over typically rough rocky glacier terrain of the Baltoro. The increase in altitude was so gradual I didn't notice it very much as I trekked higher and higher.

We stopped after about three hours for a snack lunch, cheese and biscuits, apricots and sometimes milk tea. The break was welcome, especially for Naqi and the porters to have a rest and refuel for the afternoon carry.

Up ahead, I kept my eye out for Gasherbrum IV, which poked its summit out of the clouds for a minute as I trekked from Khoburtse to Goro II.

We also passed a small beautiful green river flowing on the top of the Baltoro Glacier next to ice mounds.

We finished our trek from Khoburtse in cloudy weather at our camp of the night at Goro II (4320m). In the evening, however, the clouds started to lift.

Gasherbrum IV is a sensational sunset mountain. The summit started to poke out of the clouds, seen from Goro II.

I got my first spectacular view of Masherbrum (7821m, the 24th highest peak in the world). Originally called K1, Masherbrum is a spectacular rock and ice peak, rising to the south of the Baltoro Glacier.

‘Towards sunset there was a clearing among the clouds, and, right opposite to use across the glacier, the veil was swiftly drawn aside and disclosed the glorious form of Masherbrum (25,676 feet), his summit rocks golden in the sunlight, and grand skirts of snow sweeping down to the glacier beneath. The highest point stood out like a jutting buttress and looked inaccessible from this side.’ – Climbing and Exploration in the Karakoram Himalayas by William Martin Conway (published 1894).

The next morning dawned clear with the first rays of the sun hitting Masherbrum with its ice cream cone top glistening in the sun.

The summit of Masherbrum's sheer north face is a perfect pyramid, with steep narrow ridges rising suddenly to a sharp pinnacle. It was first climbed via the south west face on July 6, 1960 by George Bell and Willi Unsoeld on an American - Pakistani expedition. Two few days later on July 8, expedition leader Nick Clinch and Pakistani Captain Jawed Akhter Khan also reached the summit.

When I looked to the trail ahead past the ice penitentes on the Baltoro Glacier and could see the sun coming over the top of the Gasherbrum IV's (7925m) west face with Gasherbrum II just barely visible peeking out to its right.

The view of the Gasherbrums stretched across the horizon with the ridge from the summit of Gasherbrum IV dipping to a col (6493m) before rising to Gasherbrum VII (6955m), the Gasherbrum Twins (6882m), Gasherbrum V (7147m) and on to Gasherbrum VI (7003m).

Wow! Spectacular.

Day 9 June 19 Goro II to Concordia

After a beautiful sunrise at Goro II, we started our trek towards Concordia.

The Muztagh Tower came into view soon after leaving Goro II at the head of the Younghusband / Biango Glacier.

Taken from the upper Baltoro Glacier, the twin summits of Muztagh Tower (7274m) are perfectly aligned and the mountain is seen as a slender tooth, looking impregnable.

A similar photo by Vittorio Sella in 1909 inspired two expeditions to race for the first ascent in 1956. In reality both teams found their routes less steep than Sella's view had suggested.

Joe Brown and Ian McNaught-Davis climbed from the west side of the peak and reached the west summit of Muztagh Tower (7270m) on July 6, 1956.

Tom Patey and John Hartog repeated the ascent the next day, also reaching the slightly higher east summit (7274m).

A few days later a French Team of Guido Magnone, Robert Paragot, André Contamine, and Paul Keller climbed the mountain from the east.

I trekked along the upper Baltoro Glacier passing by Muztagh Tower and the nice silhouette of the U shaped Mitre Peak (6025m) before looking to the right to see the Biarchedi Glacier leading up to the long ridge to the partially cloud covered Ghandogoro Ri (6810m).

The route over the Ghandogoro La is often part of treks to K2 with the return trip through Hunza. I was happy that this was not part of my itinerary since returning the same way allowed me to see some of the mountains and spires I had missed because of bad weather.

I continued up the Baltoro Glacier towards Concordia with Gasherbrum IV (colloquially called G4) dead ahead. The slightly taller Gasherbrum II (G2, 8035m) looms over G4's shoulder.

Gasherbrum IV would probably be a more popular climbing mountain if it was 75m taller. At 7925m, it is the 17th highest mountain in the world.

Gasherbrum II (G2) is over the 8000m mark at 8035m and is a far easier peak, so it is a fairly popular climb. Fritz Moravec led an expedition of 5 climbers, a geologist and doctor to Gasherbrum II in 1956. After setting up Camp I (6000m) they had to descend in bad weather. This was lucky because when they went back up on June 30, they found Camp I completely buried under a huge avalanche. They had lost most of their food and nearly all the high-altitude equipment. Rather than descend they decided on a fast, lightly mounted attempt on the summit. In just four days they opened up a new route over very steep snow and ice slopes as far as 7000m. They then decided to make a rapid bid for the summit with a bivouac halfway.

Moravec, Larch and Willenpart left Camp III in the afternoon of July 6, climbing unroped in bad snow, bivouacking at 7500m. They started at dawn the next day in fine weather and plodded painfully on, metre by metre in deep snow. Fritz Moravec, Sepp Larch and Hans Willenpart completed the first ascent of Gasherbrum II summit on July 7, 1956 at 13:30. "On the summit, the wind was still, and we enjoyed the unforgettable wonderful view. ... The ascent of Gasherbrum II was not a victory over the mountain. The mountain was kind to us. The weather and the circumstances were good."

Broad Peak (8047m) came into view before reaching Concordia. Its name was originally set as K3, right after the famed K2. But when Sir Martin Conway saw the peak in close detail, with its summit over a mile long, he named it ‘Broad Peak’ which has stuck to this day.

Our campsite at Concordia (4745m) is beautifully situated below Mitre Peak. Concordia was named by Sir Martin Conway in 1892 after the Place de la Concorde in Paris. Concordia is the junction of Baltoro Glacier, Godwin Austin Glacier (descending from K2), and the Upper Baltoro Glacier. The view from all around is incredible.

After arriving at Concordia (4745m), my tent and the kitchen tent were quickly set up, and I enjoyed my lunch in the warm mid-day sun. The Pakistani Army are present at Concordia, with the communications line snaking through the campsite.

The clouds that hung over K2 for most of the day started to clear in the late afternoon revealing the beautiful K2 seen from Concordia. The first ascent of K2 was completed by Italians Lino Lacedelli and Achille Campagnoni on July 30, 1954. The previous day Campagnoni and Lino Lacadelli had climbed to Camp IX, with Walter Bonatti and HAP Mahdi following carrying their oxygen bottles. But Campagnoni intentionally moved the camp from the planned site so Bonatti could not try for the summit. After waiting in vain for Lacedelli and Campagnoni to appear, Bonatti and Mahdi had to suffer through a bivouac at 8100m, with Madhi suffering frostbitten toes. Controversy struck when the expedition leaders accused Walter Bonatti of turning back before delivering needed oxygen to the lead climbers below the summit. After staying quiet for 50 years, Lacadelli finally published his view of what happened in 2004, corroborating Bonatti's story.

‘The ground was almost flat - now it was flat! We looked about us ... Above us there was nothing but blue sky ... We embraced each other, then flung ourselves down flat on the snow so that we could remove our oxygen-masks. Next we tied the two small flags – Italian and Pakistani – to an ice-axe, together with a small standard of the Italian Alpine Club.’ While Campagnoni gushes with personal satisfaction, ‘it would probably be true to say that we had both just experienced the greatest moment of our lies’, Desio hits the nationalistic tone: ‘Lift up your hearts, dear comrades! By your efforts you have won great glory for your native land ... to-day all Italians are rising to acclaim you as worthy champions of your race.’ – from Ascent Of K2: Second Highest Peak In The World by Ardito Desio.

The K2 West Face shines in the late afternoon sun from Concordia. The K2 West Ridge is on the far left. The Southwest Pillar separates the sunny west face from the K2 South Face. The Mushroom is the large hanging glacier on the lower part of the Southwest Pillar. The South-southeast Spur arrives at the K2 Shoulder on the far right. The Great Serac is just in shadow to the right below the K2 Summit. The K2 Shoulder is farther down to the right, partially in the sun.

The K2 West Ridge was first climbed by Japanese Eiho Otani and Pakistani Nazir Sabir, reaching the K2 summit on August 7, 1981.

The clouds covering the summit of Gasherbrum IV cleared a bit to reveal the summit ridge and the west face at sunset seen from Concordia.

The first ascent of Gasherbrum IV was made via the northeast ridge on August 6, 1958 by famed Italian mountaineer Walter Bonatti and Carlo Mauri on a strong Italian team led by legendary climber Riccardo Cassin. ‘A desperate struggle between the mountain and ourselves, but we were all winners, and at 12.30 exactly the little pennants of Italy, Pakistan and the C.A.I. fluttered on the Summit itself. Fluttered – no, blew out in the howling gale.’ - Karakoram: The Ascent Of Gasherbrum IV by Fosco Maraini.

To the right of the Gasherbrums is the white Baltoro Kangri, and then Kondus Peak poking up slightly from the Kondus Glacier.

Kondus Peak (6756m) was first climbed on August 3, 1958 by T Kato and other climbers from the 1958 Japanese expedition to Chogolisa led by T. Kawabara.

Baltoro Kangri (Golden Throne, 7312m) is an enormous dome of snow and ice capped with five summits, seen here from Concordia in the late afternoon. ‘To it I gave the name Golden Throne (23,600 feet), for it is throne-like in form, and there are traces of gold in its volcanic substance,’ - Climbing and Exploration in the Karakoram Himalayas by William Martin Conway (published 1894).

Baltoro Kangri V (southeast, 7260 m) was first climbed by James Belaieff, Piero Ghiglione and Andre Roch, on August 3, 1934, who then skied down from over 7000m. The other four summits were climbed by two Japanese expeditions in 1963 and 1976.

I looked down the Baltoro Glacier from Concordia at sunset to see Paiju Peak, Choricho, Uli Biaho, Trango Towers, and Cathedral Peak, and Lobsang Spire.

After the sun had vanished from the other mountains, I then turned my attention back to the highest one, K2, to catch the last rays of sunset light up the top of K2’s West Face and flicker off a small cloud floating near the summit of K2.

Then I went to the dining tent and enjoyed a delicious meal followed by folk tales told by Naqi. Iqbal translated for me so I could fully enjoy the story.

Then it was off to my tent and bed to rest after a near perfect day and dream of what the next day would bring.

The next morning I was up before dawn to catch the sunrise. Gasherbrum IV (7925m) was fully clear before sunrise with the northwest ridge on the left.

The 3000m high Gasherbrum IV West Face was climbed by Robert Schauer and Wojciech Kurtyka in an alpine push between July 13 and 20, 1985. After reaching the North Summit, bad weather and extreme exhaustion forced them to descend, missing the main summit. Their climb was selected by Climbing magazine as the greatest Himalayan climb of the 20th century.

I’m ready to capture the early morning light changes on K2. I find a good rock at the entrance to my tent as a tripod and set up my camera awaiting the light show. Slowly the darkness recedes into the purples of pre-dawn light. The purples of pre-sunrise give ways to reds and yellows and white as the first light catches K2’s summit and slowly works its ways down the mountain. I hurriedly change rolls of film and continue snapping away. K2 strikes me as much steeper and even more dangerous than in pictures.

The upper part of the K2 South-South-West Ridge catches a bit of sun separating the west face in shadow from the sun descending the K2 South Face. On August 3, 1986 Wojciech Wroz, Przemyslaw Piasecki and Peter Bozik completed the first ascent of the South-South-West Ridge, called the ‘Magic Line’ by Reinhold Messner. Wroz fell to his death on the descent, apparently abseiling of the end of a fixed rope.

The South-southeast Spur is partially in the sun and arrives at the K2 Shoulder on the right. On the far right is the Abruzzi Ridge / Spur, the East-southeast ridge, the normal ascent route.

Called a suicidal route by Reinhold Messner, the K2 South Face or ‘Polish Line’ was climbed for the first time on July 7, 1986 by Jerzy Kukuczka and Tadeusz Piotrowski. Piotrowski fell to his death on the descent.

Doug Scott, Roger-Baxter Jones, Jean Afanassieff and Andy Parkin climbed the south-south-east spur in 1983 but had to retreat just 200m below the Shoulder when Jean developed symptoms of cerebral oedema. Tomo Cesan claimed he climbed the spur to the Shoulder solo on August 4, 1986 and then descended the Abruzzi Spur, although nobody saw him. In 1994 a strong Spanish team completed the south-south-east spur, with Alberto and Felix Inurrategi, Juanito Oiarzabal, Enríque de Pablo, and Juan Tomas reaching the K2 summit on June 24, 1994.

The early morning light shines on Crystal Peak and Marble Peak to the north of our campsite at Concordia.

Crystal Peak (6252m) to the left was first climbed by Sir Martin Conway on August 10, 1892 on his exploration of the Karakoram.

The jagged outline of Marble Peak (6256m) with its sharply pointed summit is on the right.

The three summits of Broad Peak are seen at sunrise from Concordia. The North Summit is on the far left, the Central Summit is in the middle with just a touch of sun, and on the far right is the Main Summit.

The first ascent of Broad Peak was completed by Marcus Schmuck, Fritz Wintersteller, Kurt Diemberger, and Hermann Buhl on June 9, 1957. This extremely small expedition marked a major step forward in the development of Himalayan climbing. Diemberger: ‘[Buhl's] plan was that from base camp onwards there would only be climbers on the mountain; they would do everything, load-carrying, establishment of camps and, finally, the assault on the summit. And it was all to be done without the use of oxygen.’ Diemberger reached the summit just as Marcus Schmuck and Fritz Wintersteller started their descent. As Diemberger was descending from the summit he met Buhl still ascending. ‘Slowly, with all that incredible strength of his will, he started to move, very slowly, upwards. ... Two men were standing on a peak, still breathing heavily from the ascent, their limbs weary - but they did not notice it; for the all-enveloping glory of the sun's low light had encompassed them too. Deeper and deeper grew the colours. ... No dream-picture, this. It was real enough, and it happened on the 26,404-foot summit of Broad Peak.’ – Summits And Secrets by Kurt Diemberger.

Here is a close up of the Broad Peak Central Summit and the Broad Peak Main Summit just after sunrise from Concordia. The first ascent of the Broad Peak Central or Middle summit was completed by Poles Kazimierz Glazek and Janusz Kulis on July 28, 1975 while three other members huddled 40m away and a few metres lower.

During the descent the weather worsened. Bohdan Nowaczyk was killed when the rope anchor failed. Andrzej Sikorski slipped, knocking Marek Kesicki and Kulis off. Only Kulis survived the fall. Kulis and Glazek eventually made it back to the expedition's top camp. Both were frostbitten, Kulis subsequently losing most of his toes.

Day 10 June 20 Concordia To Shakring

As I trekked away from Concordia, I had to stop often to look up the Godwin Austen Glacier to the beauty of K2. The Godwin Austen Glacier is named after early explorer Henry Haversham Godwin-Austen.

I knew from my research that there was another beautiful peak to the left of K2 and watched it come and more and more into view. The pyramidal summit of Angel Peak or Angel Sar or Angelus Peak (6858m) lies just to the west of K2.

We trekked up the medial moraine of the Upper Baltoro Glacier with a good view of the jagged peaks of Vigne Peak (6874m) across the glacier.

We intermixed with a Japanese Gasherbrum expedition to cross a small stream in a part of the Upper Baltoro Glacier where you realize that you are in fact trekking on a real glacier beneath the rubble.

The west face and summit of Gasherbrum IV poked out from between two ridges as we trekked up the Upper Baltoro Glacier towards Shagring camp

On June 22, 1986 Greg Child, Tim Mcartney-Snape, and Tom Hargis climbed to the North Summit and traversed 450m horizontally to the true Gasherbrum IV Summit, completing the first ascent of the Gasherbrum IV Northwest Ridge. ‘We functioned as a single being. Now on the summit, that being, drunk with euphoria, felt suddenly as if it had been merged with sky and mountain as well to become a single, elemental entity.’ - Thin Air: Encounters In The Himalaya by Greg Child.

Gasherbrum VI, Baltoro Kangri and Kondus Peak lie ahead as we trek on the Upper Baltoro Glacier towards Shagring Camp.

The summit area of Gasherbrum VI (7003m), also called Chochordin Peak, pokes above an intervening ridge as we trek on the Upper Baltoro Glacier towards Shagring Camp.

There was a large green glacial lake on the Upper Baltoro Glacier with Mitre Peak behind, as we trekked towards Shagring Camp.

We camped at Shagring (4853m) near the junction of the Upper Baltoro and Abruzzi Glaciers. Baltoro Kangri towers just beyond the camp.

After lunch, I lazed around in my tent, reading and sticking my head out to gaze at the mountain views, especially Chogolisa.

Chogolisa (7665m) is a high snow peak with a distinctive long, almost level summit ridge. Chogolisa I (7665m) is the southwest summit on the left.

The slightly lower northeast summit Chogolisa II (7654m) was named Bride Peak by Sir Martin Conway in 1892.

In 1909, a party led by Duke of the Abruzzi reached 7500m before being stopped by bad weather.

On August 4, 1958 a Japanese expedition organized by the Academic Alpine Club of Kyoto led by Takeo Kawabara made the first ascent of Chogolisa II, with Masao Fujihira and Kazumasa Hirai reaching the summit.

Hermann Buhl and Kurt Diemberger attempted Chogolisa in 1957 after they had successfully summited Broad Peak a few weeks earlier. On June 25 they left camp I and camped in a saddle at 6706m on the southwest ridge. Bad weather forced them to retreat and on June 27 Buhl fell through a cornice and disappeared. His body has never been found.

The first ascent of Chogolisa I (7665m) was made on August 2, 1975 by Fred Pressl and Gustav Ammerer of an Austrian expedition led by Eduard Koblmuller. Koblmuller almost suffered the same fate as Hermann Buhl, as he also fell through a cornice on the ascent; fortunately, he was roped and team members were able to pull him to safety.

Day 11 June 21 Shagring To Gasherbrum Base Camp And Return

The next morning we started our trek to Gasherbrum base camp in mostly cloudy weather. After 30 minutes we reached ‘Gasherbrum Corner’ at the junction of the Upper Baltoro Glacier with the tributary Abruzzi Glacier. Gasherbrum I and Gasherbrum I South lie straight ahead.

Gasherbrum I (8080m) is the 11th highest mountain in the world. Gasherbrum I was first climbed by July 5, 1958 by Americans Pete Schoening and Andy Kauffman.

'We came over the rise and there it was – Hidden Peak. ... The shape was familiar but the size was beyond belief. In front of us and 10,000 feet above our heads, at the top of a gigantic pyramid that rises directly out of the South Gasherbrum and Abruzzi glaciers, was the summit. Just below it, a glacier tumbled down the mountain underneath the tremendous hanging ice cliffs of the west face. To the left, the bare rock of the northwest ridge swept up the final pyramid.' - Nick Clinch, A Walk In The Sky

"To the right the French buttress climbed into the sky and culminated in the point called Hidden South (23,200 feet) before connecting with the high snow plateau that extends for miles toward the southeast at an elevation of over 23,000 feet. Beyond the French spur, almost out of the scene, the arête tried by Andre Roch in 1934 rose for thousands of feet before it too, joined the plateau, five miles from the summit. For years we had been mentally climbing Hidden Peak." - Nick Clinch, A Walk In The Sky

Gasherbrum I South (7069m) was first climbed by Maurice Barrard and Georges Narbaud via the Southwest Ridge in July 1980 on their ascent of Gasherbrum I.

The clouds hid the mountain views as we neared Gasherbrum Base Camp on the Abruzzi Glacier. Oh well. After a quick lunch at Gasherbrum Base Camp, we retraced our steps to Shagring camp.

Day 12 June 22 Shagring To Concordia

When I woke the next morning at Shagring camp on the Upper Baltoro Glacier, snow had started to fall on the kitchen tent.

We trekked back from Shagring camp to Concordia in cloudy weather. I admired the cutaway view of the glacier, clearly showing that the rocks, gravel and rubble on the surface hid the true glacier just below. We arrived back in Concordia with the weather still not improving.

I went to bed dreaming of finally reaching K2 base camp the next day. The crew stayed up a little longer in their kitchen tent, talking and singing.

Day 13 June 23 Concordia To Khoburtse

The next day I poked my head out of my tent at Concordia to see a snowfall. I talked to my guide Iqbal and he said that even if the snow ended by the end of the day, we’d probably have to wait a few days for the trail to base camp to be safe. But, Nanga Parbat beckoned, so I decided to retreat.

We packed up at Concordia and trekked back down the Baltoro Glacier in snowy cloudy weather to Khoburtse. It started to clear in the evening and the next day dawned perfectly clear.

Return To Skardu

Day 14 June 24 Khoburtse To Paiju

Day 15 June 25 Paiju To Korophon

Day 16 June 26 Korophon To Skardu

We then trekked back to Askole via Jhola and Korophon in perfect weather, and then via jeep to Skardu.

We stopped for a coke in a green oasis on the drive from Thongol to Skardu to celebrate our successful trek. From left to right: cook Ali, porter Hayder Khan, sirdar Ali Naqi, porter Muhammad Khan, Jerome Ryan, porter Muhammad Siddiq, and guide Iqbal.